Decoding the FDA Guidance on Essential Drug Delivery Outputs

By Life Science Connect Editorial Staff

The FDA’s draft guidance Essential Drug Delivery Outputs for Devices Intended to Deliver Drugs and Biological Products discusses general concepts around what were formerly known as essential performance requirements (EPRs), now referred to as essential drug delivery outputs (EDDOs). To understand the guidance’s potential impact, it is necessary to explore the reasons behind the change as well as the document’s treatment of device development topics such as design outputs, verification/validation, and control strategy.

Why Change from EPRs to EDDOs?

The EDDO guidance is not a major change so much as a nuanced makeover; its foundation was established in guidance documents including Container Closure Systems for Packaging Human Drugs and Biologics and Q8(R2) Pharmaceutical Development. The former requires OEMs to assess the ability of their container closure system to function as designed; the latter contains stipulations around quality by design (QbD), accurate and reproducible drug delivery, and simulated use of the drug product for test conditions.

However, industry feedback to the FDA revealed confusion about the term “essential performance,” particularly its overlap with similar terminology in documents such as IEC 60601-1-11:2015, Medical Electrical Equipment. Accordingly, the change to EDDO from EPR is part of the agency’s effort to align the guidance’s terminology with that in the design control regulation. The FDA is stating that EDDOs are a design output-driven concept, versus the design input-driven concept of EPRs.

In terms of precedent, for example, ICH Q12: Implementation Considerations for FDA-Regulated Products instructs readers to determine essential conditions by assessing product characteristics critical to the product’s safe and proper use. That language is footnoted from ISO 13485. Under the new guidance, the FDA describes EDDOs as device functions necessary for delivery of the intended drug dose to the target site — from preparation to initiation, progression, and completion of dose administration — aligned with the specifications and labeling for the product.

Identifying EDDOs

The positioning of risk mitigation activities in the development process is a helpful differentiator in identifying what is output-driven rather than input-driven and, therefore, may need to be declared an EDDO. For example, under ISO 11608-1:2022 Needle-based injection systems for medical use — Requirements and test methods, designers filter out primary functions based on risks, whereas EDDOs are inherent to the design features. So the EDDO concept is more broadly focused on control strategy relevant to design outputs.

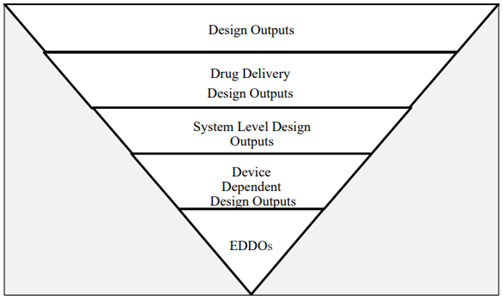

Fig. 1 — Illustration of the EDDO identification process

Fig. 1 depicts an Illustration from the guidance that clarifies EDDO identification, starting with design outputs. These outputs are derived by translating user needs into design inputs based on the intended users and the use environment. From this information, specific design specifications arise, including route of administration, drug characteristics, dosage form, and delivery volume.

Next, the subset of design outputs related to drug delivery is determined: intended dose, target site for delivery, and route of administration/delivery method. Reconstitution or product preparation prior to drug administration fall under this category, as do functions necessary for final product performance, such as glide force and needle characteristics.

Importantly, system level design outputs are independent of the user and, instead, are dependent on device design. Thus, EDDOs apply to the device and to device constituent parts of CDER-led and CBER-led combination products (i.e., drug-led and biologic-led combination products). However, CDRH-led combination products already have this concept of essential design outputs, so the EDDOs do not apply.

Citing an example from the guidance, a prefilled syringe user administers a drug dose: If the instructions for use (IFU) state the user must hold the needle at a 45-degree angle to the skin and then pinch the targeted skin before administering the drug, those stipulations are not dependent on device design. Rather, those instructions depend on the user. Conversely, device attributes like break-loose force, glide force, and needle safety activation force depend on device design.

Apply Product-Specific Design Verification

The EDDO guidance aims to provide the FDA with flexibility when determining the type of performance data (e.g., preconditioning, reliability, and sample size) the agency requires for specific device types. For example, in the case of an auto-injector, testing conducted per ISO 11608 generally will remain applicable. Still, the FDA included high expectations in the guidance relevant to preconditioning.

The guidance states EDDOs depend on the conditions a product will be exposed to during production, shipping, storage, and preparation, as well as the conditions specifically associated with its use. Therefore, developers must map product development progress carefully so the product can be appropriately preconditioned. Preconditioning and reliability assessment typically consider three main categories: shipping, shelf life, and “other,” which can comprise product-specific risks and scenarios.

The guidance’s verification section is broad in terms of overall testing considerations, so consider a phase-appropriate approach when determining when testing is conducted and verification data are applicable. The same type or level of information may not be applicable or expected at the clinical development phase versus the commercial phase.

A Different Take on Design Validation

Even though design validation typically encompasses elements tied to device users, such as human factors, the EDDO guidance includes a requirement to perform design validation relative to the EDDOs. This requirement focuses specifically on device functions that are design outputs, confirming those outputs have met all input requirements.

The logic is that some design outputs have a relationship to the user in terms of their capability, such as a device’s dose accuracy. Each EDDO for drug delivery should be considered in the context of why the specification, as written, is applicable to meeting the intended use and user needs. FDA review teams receive information broadly across premarket approval (PMA) applications to answer some of these questions, so things like dose accuracy often are addressed as part of clinical development — depending on how the devices were implemented or bridged from that part of the process.

The EDDO guidance’s overall intent is to focus on device design features and their performance. Device developers must be able to perform that assessment on a product type-by-product type basis and, based on the device’s intended uses and what is described in the IFU, determine whether those features are device-dependent or depend on an outside element, such as the user.

An Attempt to Streamline Control Strategy & Release Testing

Device designers are accustomed to implementing an array of controls, but per the guidance, each EDDO identified must be accompanied by an effective control strategy. The guidance stipulates a need to include purchasing controls and in-process controls — of process parameters, incoming materials, and downstream testing. Developers also need to assess the effectiveness of upstream controls on downstream performance. Linking risk analysis between upstream and downstream controls is key to EDDO risk analysis.

Additionally, the FDA is attempting to be more flexible in terms of the information it expects relevant to the scope and the breadth of control strategy, directly tied to product. Not long ago, the FDA’s approach was to ask for release testing for all EPRs, an approach that generated significant industry pushback. Now, the agency focuses on more targeted questions about the product.

Finally, some emergency use products have been acknowledged by FDA as having an expectation of greater product risk, so the control strategy scope is subject to more scrutiny and the breadth of controls is subject to more targeted questions. The extent of the FDA’s assessment in these scenarios may rely on the totality of design verification and validation data, both in terms of how thoroughly the information demonstrates product performance stability and how susceptible the technology is to degraded performance based on certain manufacturing elements. In short, the FDA is looking at product-specific risk considerations as well as technological and manufacturing process-specific risk considerations.

Post-Approval Change Advice is Scant

The EDDO guidance does not provide a lot of clarity about what types of changes would require post-approval submissions, partly because that information falls outside the scope of the guidance. Also, the agency reportedly is working on a guidance covering post-approval changes. Additionally, some of the pathways described here, such as 510(K) or PMA, already have well-established post-market change policies in place.

From this standpoint, a great opportunity exists to align the ICH Q12 implementation considerations draft guidance with the EDDO guidance. The ICH Q12 guidance discusses how to ensure primary characteristics are being verified and/or validated, as appropriate, for post-market changes. Conversely, the EDDO guidance states that all EDDOs need to be assessed for the potential impact of post-market changes, requiring reverification, revalidation, or both for any potentially impacted EDDOs.

In ICHQ 12, there was an effort to foster a mindset of “essential conditions,” phrasing commonly used in the drug world but not in the device world (where the equivalent is EDDOs). EDDOs do not comprise all essential conditions surrounding the device itself versus the processes being used to ensure device performance is maintained. The guidance states that developers can consider EDDOs as a subset of critical quality attributes (CQAs), even suggesting developers include EDDOs and established conditions into the quality target product profile (QTPP). This is a good start toward clarification, but additional opportunities still exist.

EDDO Guidance is Just the First Step Toward Clarification

Per the guidance, EDDOs are “design outputs necessary to ensure delivery of the intended drug dose to the intended delivery site.” As simple as that sounds, the document is filled with nuance. The FDA continues to clarify its intent, and subsequent guidance documents should help to remove ambiguity from the current document. Helpfully, several tables are included at the end of the document that provide examples of identifying and clarifying EDDOs.

Device developers can map an approval process relevant to their specific product using those resources and the approaches described here. To learn more, read Drug Delivery Leader Executive Editor Fran DeGrazio’s commentary, Understanding Essential Drug Delivery Outputs: Things To Know About EDDOs, and watch the associated Drug Delivery Leader Live event, The FDA Guidance on EDDO: What to Know, What to Do.